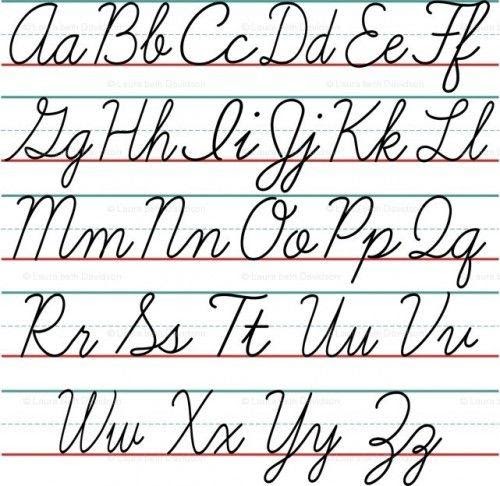

This blog is old school—literally, old school. If you’re above a certain age, you’ll remember seeing this, usually stretched out above the blackboard, in grade school:

Prior to 2009, every child, upon reaching the third grade, would learn cursive. By the end of third grade, schoolwork would be done exclusively using cursive, and in the fifth grade, if your cursive was neat enough, you got to write in ink. Writing in ink meant you had arrived; you were practically an adult.

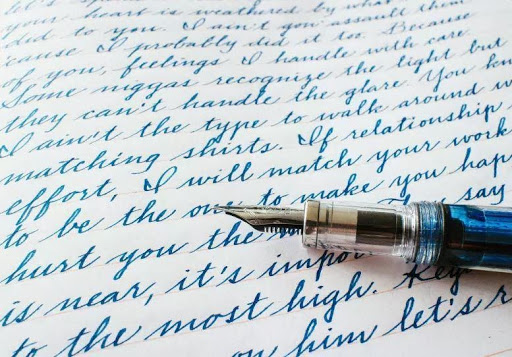

At one time, when people communicated using pen and paper, cursive was the common currency. No one printed their letters—printing was for very young children—and typewriters were used more for formal or business communications. If one were writing anything—from a shopping list to a thank-you note to a school essay—cursive is what was used.

Cursive wasn’t only a means of written communication; it was an act of self-expression. Writing in cursive was an art. More importantly, a person’s cursive handwriting not only identified them, but told you something about them. Check out these two handwriting samples, courtesy of Election Academy and BuzzFeed, and see if you can form a mental picture of the writers:

Not only was one’s handwriting unique, but one’s hand-written signature was a nearly un-duplicatable form of identification. Cursive signatures were difficult to forge and were remarkably consistent throughout one’s life. Your signature proved that you were you.

Cursive Disappears

As pervasive as cursive handwriting was in American culture, the teaching of cursive began to lose steam in the latter half of the last century. With limited school budgets, many educators thought that resources could be better spent on other subjects, and with ever-increasing time being spent on standardized testing prep, many school districts deemed cursive an unnecessary skill, taking too much valuable time to teach.

With computers, phones and tablets becoming ubiquitous in the mid-2000s, hardly anyone needed a pen and paper for anything, and cursive seemed even more irrelevant.

The final blow came in 2009 when states banded together to launch Common Core State Standards. Those standards recognized students’ use of keyboarding as opposed to writing and dropped cursive from the suggested curricula of schools. By 2012, 47 states no longer taught cursive. It was considered a “dying art” and it was felt this outdated art had been replaced by technology.

Cursive Makes a Comeback

Within a few years, however, many Americans realized that unfamiliarity with cursive might be problematic. For example, one can certainly read the Constitution of the United States, the Declaration of Independence, or the Gettysburg Address online, but to read them in their handwritten form adds a personalization that seeing them on an iPhone lacks.

Another problem with not knowing cursive is that it isolates those who are cursive illiterates, separating them from the multiple generations who still use it. No child wants to feel alienated.

And so, just when it looked like learning cursive was down for the count, states began changing their minds, reinstating cursive in their curricula.

What’s So Good About Cursive?

Those who would eliminate cursive from schools are only seeing it as an outmoded form of messaging, and if that’s how one looks at it, then switching exclusively to keyboarding makes sense. However, learning to write in cursive has several proven collateral benefits that children can draw upon for the rest of their lives. According to Psychology Today, those benefits include:

- Eye-Hand Coordination – Learning a skill like throwing and catching a ball requires that the brain create new circuitry to evaluate what is seen, what movements are required, and to estimate speed and predict a ball’s future location. This developed circuitry is permanent and can be called into action in other situations. Learning cursive employs similar skills, additionally requiring constant adaptation, thought and flexibility as every written word demands a different motion and it’s all done while thinking about what is being written.

- Task Mastery – Cursive may be a complicated skill, but it is one that can be mastered by any child. From learning the motor skills of how to hold a pencil or pen, moving it deliberately to form letters, how to move the hand and arm, honing memory skills in recalling the letters and how they connect to each other, paying attention to what letters have been written and what letters are to come—all of these important skills are constantly used when learning cursive and, as a child masters these skills, their self-confidence improves.

- Increased Creativity – Using cursive is a way of expressing one’s self, as each letter can be creatively constructed. The writer can fine tune the shape of the letters and words as one would if creating a work of art. And because writing in cursive is a slower process than keyboarding, the writer has time to think, imagine, create and craft, not just the message, but how the message is conveyed.

Additionally, a report from PBS claims that writing in cursive can be a real help to those coping with dyslexia. According to Marilyn Zecher, a language specialist at the Atlantic Seaboard Dyslexia Education Center, students with dyslexia have difficulty learning to read because their brains associate sounds and letter combinations inefficiently. But cursive can help them with the decoding process because it integrates hand-eye coordination, fine motor skills and other brain and memory functions.

In 2016, the Arizona Board of Education amended the Common Core Standards and became the first state to require that cursive again be taught in elementary school, beginning in the third grade. Today, more than half the states have returned to curricula that includes cursive.

Unfortunately, those who endorse cursive are, in all likelihood, fighting a battle that will eventually be lost. Many young educators feel that including cursive in a school’s curriculum is an idea pushed primarily by baby boomers who are trying to bring back those nostalgic days of yesteryear, and they may be right. As memories of the days when cursive was ubiquitously used for everything begin to fade, those supporting keyboarding will likely win this battle.

In the meantime, though, it’s nice to know that the tradition of cursive—which can be traced from ancient Rome in the 1st century BC, to Charlemagne in 781 AD, to modern English—is an art that will be learned by at least one more generation of students.